Digital art is continuously developing and is

generally qualified as art work that incorporates technology and computers. It

has evolved into a diverse collection of practices that range from

object-oriented works to those art forms that integrate dynamic and interactive

elements with a process-driven virtual form.

The Internet has afforded many individuals a global

platform and exchange of information. For artists, the advent of the World Wide

Web and recent developments in wireless technologies and mobile devices enhance

the means of accessibility and mass circulation of artwork[1].

In addition, there has been a growing enterprise and popularity of

gaming. Currently, it is considered to be a billion dollar industry which has

been an important factor in the ‘digital revolution’ as it has explored many

paradigms that are now common in interactive art.[2] It

has become increasingly more lucrative and exceeds the film industry. Artists

have given games a different value other than entertainment or fun when it

merges and engages with culture. Pippin Bar is an artist who operates

within the realm of the Internet and combines both text and the tactics of

games to express and distribute his messages and work. He uses the structures

of games as a means of creative expression, as instruments for conceptual

thinking and as tools to help examine social issues and the world around us.

There is a wide variety of genres of games which includes strategic, shooters,

god games, and action.

Several successful video games are extremely

violent ‘shooters’ genre. Hence, it seems only likely that digital artworks

would critically investigate their interactive predecessors and counterparts

and explore their paradigms in a different context[3].

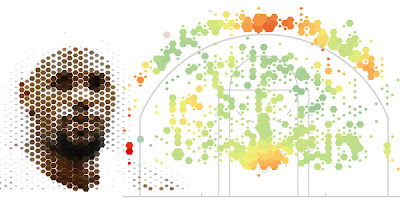

Video games such as, Barr’s War Game (2012) is an action

shooter game that explores the human psyche through a seemingly endless cycle

of fighting and self evaluation.

War Game [4]has

visual similarities to old halcyon handheld LCD games and Barr creates it with

features such as beep sounds, slow refresh rates and intentional glitches. As

the game progresses and as the user is further injured, the more glitches are

experienced. The glitches begin to take the form of civilians, letters and

harmful bombs. As the player is injured there is a mandatory mental health self

evaluation where the player expresses his/her own thoughts in 100 characters or

less on war, fighting and family. The glitches make everything difficult to

read and metaphorically appear that the soldier’s judgments and mental

constructs are slowly deteriorating every time the soldier is forced to fight

or experience more battles. Throughout history, there has been a mental illness

that is caused by war presently referred to as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Military combat is one the potential sources of this condition. The recent wars

in Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted in increased military related suicides.

In the year of 2009, approximately 1500 veterans who were deployed or

experienced these wars have made suicide attempts[5]. This aspect of the game is a commentary on the

mistreatment of military veterans and the effects on their health.

Additionally, in War Game, Barr

shows a human condition of fighting where it does not make sense, there are no

sides and there is no identity for the opponent. The game evokes rhetorical

questions such as, does the player even care about who is the opposition and

why the player is fighting this battle. The game is not sensible with

enticingly unconventional and unsolvable game goals that are not articulated.

Text becomes a vital element in the game. The decision of making the psyche

evaluation 100 characters in War Game makes a profound effect

on how the game operates. The limitation can suggest oppression as the player’s

answer is cut off immediately at the character limit which can also be

interpreted as a metaphor that the military psychologist is not listening. Barr

is making a statement on the human foibles such as excessive competitiveness

and winning against one another. There is the commentary of war being hopeless

and the question of the aspect of the play function or functionality[6].

Barr’s emphasises on the player’s process. As he is not solely the creator of

the work, Barr’s role is a facilitator for audiences’ interaction and

contribution to the artwork.

Another game is Let there be Smite! (2011)[7]:

This is a humorous god game that allows the user to play the role of God and to

decide whether to punish or forgive all the sinners in the world. The humour of

the game focuses on religion and god games. It is also a satire on the social

behaviours of humans. It equates being God as a metaphor of monotonous and tedious

desk job where the player deals with the sins of the world as they arise. Sins

are defined by the parameters of the Ten Commandments. The player can either

forgive or smite the sinner in an infinite cycle. The visual simulation is a

view of a “surveillance” camera and then popping dialog boxes that notify the

users of the sins committed by the community. As the population grows, the

speed of the sins committed increases and it becomes increasingly overwhelming

and ultimately the player may activate the panic button can be activated where

in the virtual reality a great flood occurs and washes away the sinners to

start humanity afresh. However, it is a cycle of a community that is committing

a wide range of sins. [8] During this chaos, there is the moment when the

player would no longer read and respond to the sins in an inattentive manner.

In games, it is common that players would consider their course of action,

however the game intensifies that inattentive state while proceeding in

relation to the ambiguous boundaries of accepted morals and behaviours that

should not be treated in that unmanageable way. Barr’s design creates the

impression that humanity is bound to commit sins, that humans have weaknesses

and foibles and the role of God is to decide how much can be tolerated.

Furthermore, Barr sees games as a fascinating means

to circumvent the unconscious expression and authorship itself. His strategy of

clever manipulations of data, texts, phrases and visuals contribute to

humorous, satirical and wry commentaries on art and world issues. Barr is

concerned with social issues and employs game-like structures and interactivity

as the opportunity to involve the viewers in heightened ways. Although

any experience with art is interactive, it relies on a relationship between

context and production of meaning from the audience. Thus, the

interactive experience of traditional forms resonates as a mental event in the

viewer. However, the interactivity in digital art offers different forms of

navigating, assembling, or contributing to an artwork that goes beyond this

purely mental event. The participant’s involvement is with a work confronted

with complex possibilities of remote and immediate interventions that are

unique to the digital medium[8].

Barr provides a lens through which we engage the world not just the arts but

also politics, the military, psychology and history. Barr spurs untraditional

approaches to game design and tries to foster intervention which can address

social issues.

Since the early 1990s, digital art had made

profound developments and it continues to expand. It engages audiences in a

unique process that consists of information, textual, visual and aural

components and does not reveal the artist’s intention and content at a glance.

The expansion of digital technology will continue to have a great impact on the

world. Artists often mirror their time and induce the creation of even more

artworks that reflect and critically engage life and culture. The artist

manipulates content, codes of conduct, contact conception and ways of interacting.

[4] Pippin Barr. “War Game”. Accessed October

16, 2012. http://www.pippinbarr.com/inininoutoutout/?tag=war-game

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/11/02/suicide_n_1070491.html

[6] MOMA. “ Contemporary Art Forum: Critical Play

– The Game as an Art Form”. Accessed on October 13, 2012.

http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/events/13985

[7] Pippin Barr. “War Game”. Accessed October 16,

2012. http://www.pippinbarr.com/inininoutoutout/?tag=let-there-be-smite

[8]Pippin

Barr. “War Game”. Accessed October 16, 2012. http://www.pippinbarr.com/inininoutoutout/?tag=let-there-be-smite

[9] Wong, Chee-Onn, Keechul Jung, and Joonsung

Yoon. “Interactive Art: The Art That Communicates.” Leonardo 42,

no. 2 (January 1, 2009): 180–181.